The beer that doesn’t exist

Ephemera of Bulimba

Intercity football has a long history in the Southeast. What was probably the first southeastern intercity game was played on July 30, 1870. The Ipswich Football Club, whose first training session six weeks earlier had attracted 35 members, challenged the Brisbane Football Club, established 1866, to a game in the coal mining town. Brisbane won with a single goal, with the advantage of having had some practice.

The return fixture was held on August 20 at Queen’s Park in Brisbane. Despite the completion of the railway between Brisbane and Ipswich several years earlier, fifteen players from Ipswich travelled downriver on the steamboat, Emma, to the city. After three and a half hours, two goals had been scored and Brisbane were the victors.

The laws for the 1871 match were agreed in June, referring to an amalgamated ruleset of the Brisbane and Ipswich clubs. Rugby league would not come to Australia for another four decades, and wouldn’t take on a form we recognise today for nearly a century, so the question is what kind of football Ipswich and Brisbane played at Queen’s Park?

The answer is: dunno.

The ruleset was not published but was agreed by the clubs at meetings ahead of the game. The result was a one-all draw after two hours, Ipswich kicking their first ever goal against Brisbane, before the teams retired to the Australian Hotel for dinner and toasting. Scoring the games in goals does not provide any clues, as touchdowns in proto-rugby did not score points but rather offered the opportunity to try a kick at goal (hence the name).

While some spectators would have had a frame of reference from folk football, it is entirely possible that few people in 1870s Brisbane knew the rules of any codified football, so reporters sent to watch the game may not have not have fully understood what they were seeing and could not couch their description of the matches in terms of Melbourne, Rugby or other sets of rules, as we might expect now. These were matches between a bunch of guys, mostly old boys of elite education institutions, who liked the “manly pursuit” of football and has very little to do with our present understanding of codes of football, professional sport or representative teams.

This is the primordial ooze of sport.

Sean Fagan argues that Melbourne rules (later Victorian, then Australian rules, established 1858) were a reaction to the violence of mid-19th century rugby and an attempt to make it safer and more palatable for players and spectators. So from the ooze emerges its first creatures.

But this was not a national phenomenon. To quote:

Sydney appears to have adopted the Rugby game as best it could, but in Brisbane, Adelaide, Launceston and Hobart each independently debated and then adopted a modified form of English football that suited them.

And a later quote from Tony Collins:

In fact, the founders of football in Melbourne saw themselves as being no less British than those living in Britain. They were merely engaging in the same discussions about how football should be played that were taking place among British footballers at the same time.

They fully shared the belief that football of whatever rules was a mark of Britishness and of the superiority of the British race.

In Brisbane, both Rugby and Melbourne games were played, sometimes interchangeably, within the same club by the same players. The first fixture of the intercity series in 1878 was played under Rugby rules, as proposed by the Brisbane Football Club, and the second under Melbourne rules, at the behest of Ipswich. Each team won the match played under their preferred rules.

It was strange that Brisbane preferred Rugby rules, as just two years earlier:

The clubs had begun the 1876 season voting to play Rugby rules, but it was quickly evident “the bulk of the Brisbane players do not appear to ‘savee’ [understand] the complicated Rugby code of rules newly introduced amongst us” (The Queenslander, 17 June).

While Brisbane FC had gained some understanding of Rugby by 1878, the Melbourne game was generally ascendant in Brisbane. That changed in 1882. Daniel Pring Roberts, member of the colonial legislative council, solicitor and all-round athlete, sent a challenge to Sydney’s Wallaroos on behalf of Brisbane FC to play a match under Rugby rules, with teams representing their respective colonies.

Queensland’s rugby victory in Sydney in 1886 would set in motion a train of events that would push rugby, and later rugby league, to the top of the table of Queensland’s footballing preferences.

Please allow me to briefly interrupt the story…

The Maroon Observer is entering its fourth season of publication. This operation continues solely because of an ever-growing subscriber base of people, like you, who read these newsletters. They, like you, enjoy one of the many advantages of this newsletter: no one is ever going to steal my story (except that one time that did happen).

If you want more writing about rugby league, Queensland and rugby league in Queensland, subscribe now.

If you’re already subscribed and think people you know will enjoy this, then share it with your friends and family. Word of mouth is the best way to get more people on board. Forward the email or share on social media.

Until the new NRL season kicks off in Vegas, annual paid subscriptions are 10% off. Now would be an excellent time to upgrade to paid (or renew) to get full access to the club newsletters, The Dataset™ and the privilege of leaving comments.

If you’re not in the market for a recurring subscription, you can do a one-off at Ko-fi, where I have published deleted scenes from last year’s newsletters on the basis that they were too crazy to send to actual subscribers. For just $5, you can see what’s really going on.

Now, back to the 19th century…

In 1824, a new colony was established at Moreton Bay to house the worst of the worst convicts in New South Wales. Europeans, mostly but not entirely British, explored and surveyed the land, found natural resources and sent for more Europeans to exploit them. This became the colony’s raison d’etre.

In 1842, the penal station was closed and free settlement was allowed in Moreton Bay. Four years later, roughly 1,000 settlers lived in Brisbane and Ipswich. A labour shortage developed, triggering the government to send for a boatload of skilled men, women and some street urchins on the Atremisia. More migrants arrived a year later aboard the Fortitude, chartered by John Dunmore Lang, for whom Lang Park is named, and some settled the valley which bears the ship’s name.

The Indigenous people of southern Queensland paid the price.

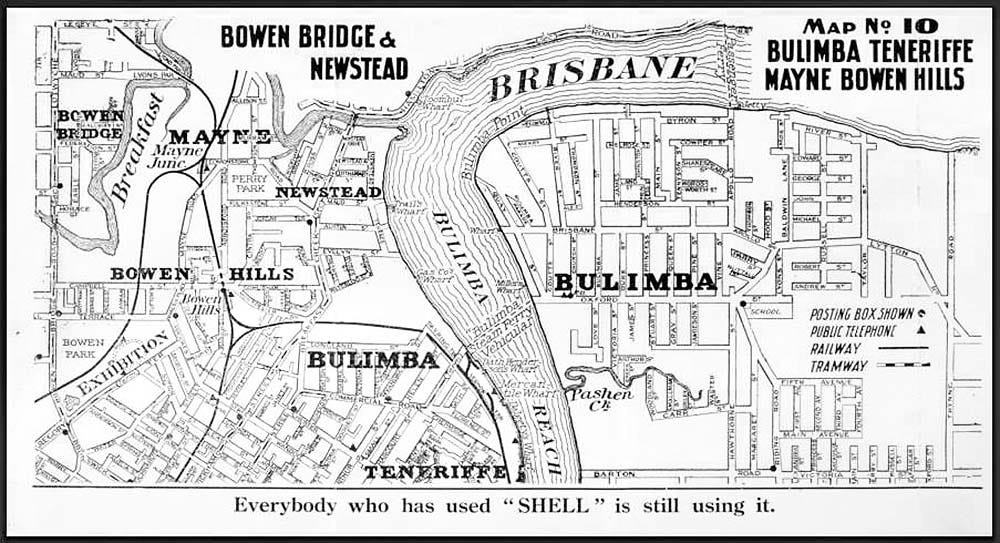

To get the resources - gold, coal, wool, sugar, grain, beef, timber, minerals - out of the land and into domestic and international markets, and without having to go via the “incubus” of Sydney, infrastructure was required. The question was whether Brisbane, the main settlement, or Ipswich, the gateway to the productive Darling Downs, would be the capital of the soon-to-be separated colony. This hung on whether the first port and associated customs house would be established at Brisbane, on the River, or at Cleveland Point, on the Bay.

As anyone who has spent more than five minutes in Cleveland can attest, it is not suitable for shipping but speculative interests, relying on a total vacuum of information about the land in the colony and grossly inflated estimates of costs to make Brisbane viable, made this a debate longer in the late 1840s than was necessary. Ultimately, sanity prevailed, Brisbane was selected and later became the capital.

In the late 19th century, railways were constructed across Queensland to transport produce to ports at Brisbane, Rockhampton and Cairns. This is the broad origination of the three parts of Queensland: railways traversed from west, where the resources were, to east, where the ports were, but not north to south. The North Coast Line, which finally connected Rockhampton to Brisbane in 1903, then to Cairns in 1924, was completed decades after the latitudinal lines had been in operation.

As described by Dr Brett Stubbs in Beers, Mines and Rails, this economic engine would reveal itself in a pattern: a mine would be built, a railway would be built to that mine to connect its output with the relevant port and along the way, a brewery would be commissioned to provide beer for the workers, usually at a pub in a town that the railway was being built to. Once the railway was complete, the brewery would go out of business, unable to compete with the much cheaper product brought in from larger cities by the very same trains that ran on the new railway.

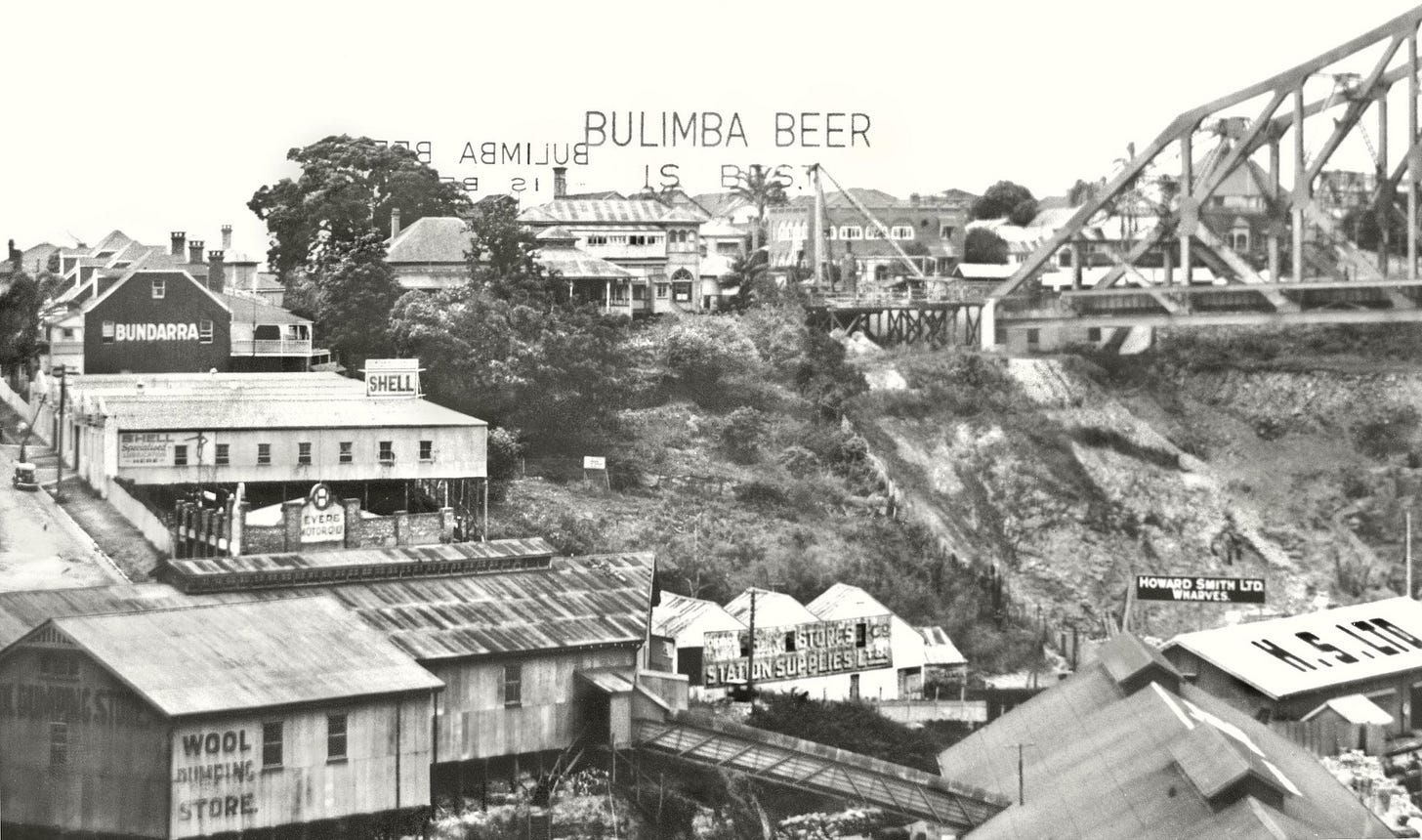

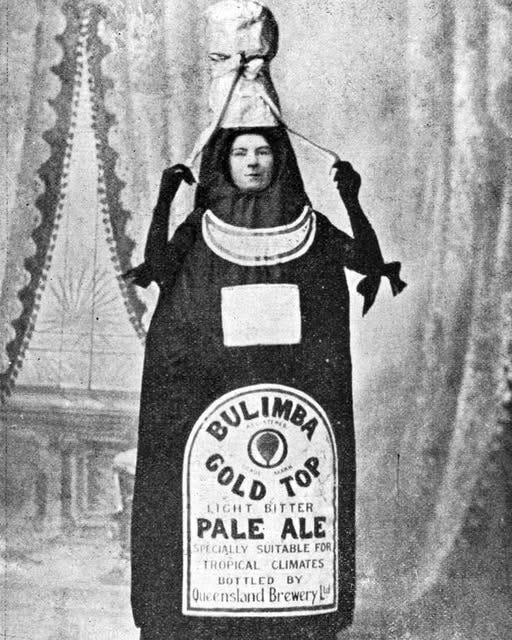

In 1882, construction began on a brewery and sugar refinery in Bulimba. That complex would become the Dalgety and Co buildings in Teneriffe but then it was the Eagle Brewery. The concern was initiated by Robert Tooth, related to the Teeth of Kent Brewery’s Tooth and Co in Sydney, and didn’t make it past May before changing hands in 1883 and then again in 1887 to become the property of Queensland Brewery Limited.

Bulimba Gold Top, the flagship beer of the Queensland Brewery, was first released in 1898. A handsome advertisement atop the masthead of Brisbane’s The Age described the new beer:

Bulimba Gold Top Light Bitter Ale is undoubtedly superior quality to anything in the market.

“Bitter ale” is what we would call an English pale ale now, although the degree that you could connect a Federation-era Australian brewery’s self-conception of its product with the actual beers of Albion, and then again with our modern understanding of what those styles represent, is questionable. Gold Top was notable as likely being the first locally brewed and bottled beer, with draught beer having been the only format available since the establishment of the first brewery in Brisbane four decades earlier.

Beer typically only has four ingredients - water, malt (sometimes in adjunction with sugar) to provide fermentables, hops and yeast - and colonial beer was a product of the Empire. While we see a transition from the darker porter beers to lighter ales and lagers as the prevailing style, beers were intended to replicate those of the mother country but the ingredients for Gold Top came from around the world. The sugar came from Mauritius in Africa, as well as Queensland. Malt, wherein grain (mostly barley, sometimes wheat) is tricked into germinating to release sugar and protein but terminated from growing into a plant, came from England. The hops came from Kent, Tasmania, New Zealand and central Europe. The only solely local ingredient in the original formulation of Gold Top was the water from Enoggera Reservoir.

30 years later, during the Depression and after the railway network was more or less completed, the state was served by the output of a dozen breweries: two operated by Queensland Brewery Ltd, one in the Valley and the other in Toowoomba, two by Castlemaine at Milton and Toowoomba, Perkins in the city and another half dozen in regional areas. Gold Top is now a product entirely of local ingredients (except for the hops, which come from Victoria) with grain sourced from the Darling Downs, sugar from North Queensland and the beer is aged for three months in barrels built in Brisbane.

Brisbane has grown from a tiny penal colony that may as well be on Mars to a functional city in the European mould with sufficient wealth and people to have a thriving consumer market.

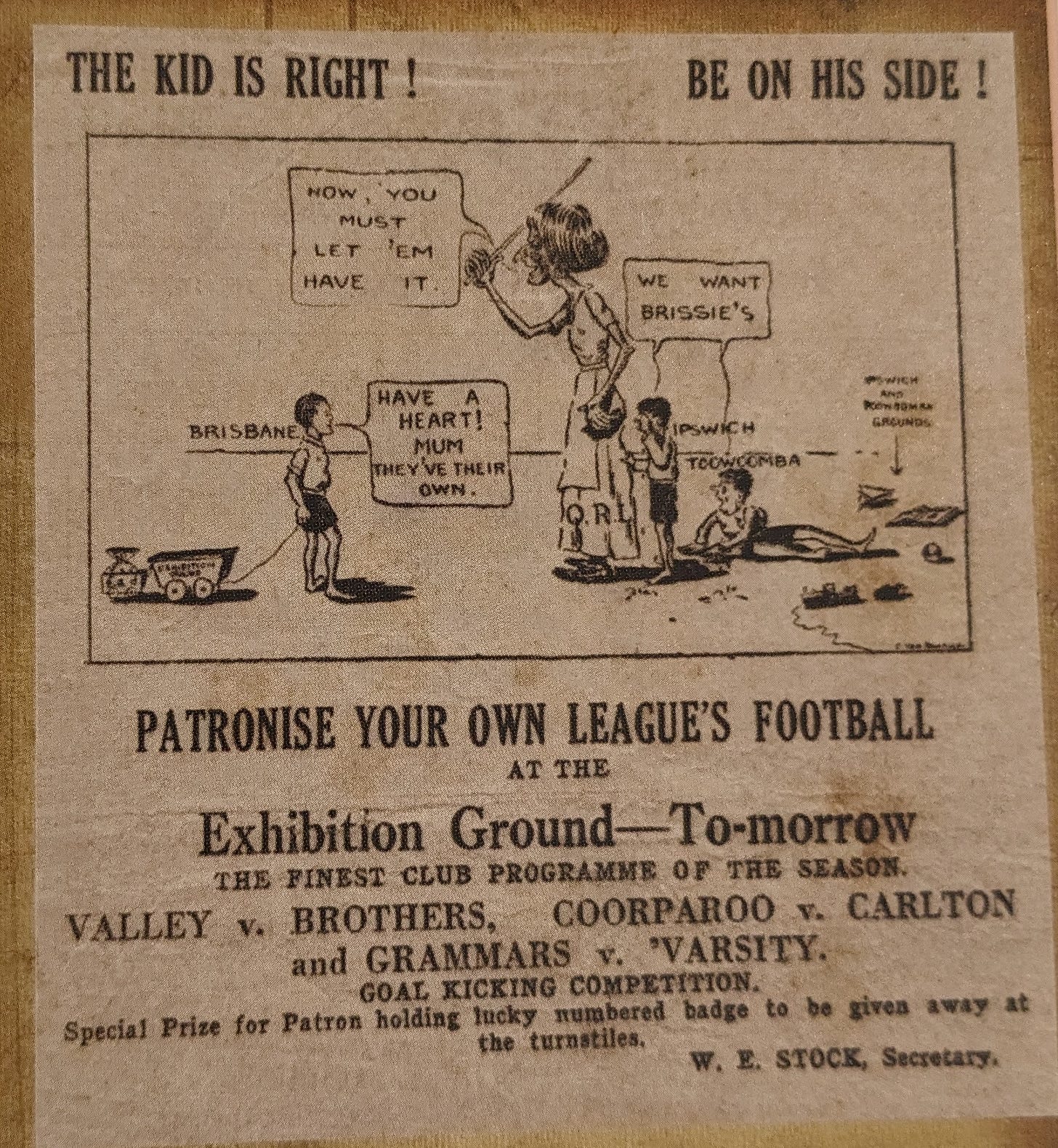

Acrimony led to a split in Queensland rugby league in 1921. Regional leagues paid an annual affiliation fee of five pounds and change to the QRL and were left to their own affairs. The Brisbane competition was directly managed by the Queensland Rugby League. The QRL gave in and passed a resolution to establish the Brisbane Rugby League as its own entity, giving control of metropolitan football to the clubs.

The QRL retained control of internationals, when played in Queensland, and interstate football. The BRL would be responsible for the club game within Brisbane. But what about intercity football?

The rising popularity of intercity games brought this question to a head. Traditionally, intercity games had been organised by issuing challenges between clubs, and later leagues, and they would be scheduled on an ad hoc basis at a time that both leagues could agree.

In 1924, Ipswich and Toowoomba were set to play a three game series under the auspices of the QRL. With one game in Ipswich and a second in Toowoomba, where would a third game be played? Would Brisbane make sense as a neutral site? If the first game was scheduled before the first interstate game, that would give the city-based selectors an opportunity to evaluate some country players they wouldn’t otherwise have. They could tack on a Possibles versus Probables curtain raiser for the metropolitan-based players. This was going to sell heaps of tickets.

The QRL wrote a letter to the BRL informing them that this is what was happening. The slate of games would be held at the Exhibition Grounds on May 17 and a third of the gate would go to Ipswich, a third to Toowoomba and the remainder would be split between the QRL and BRL. Except, because nothing ever changes, it was beyond the capability of the QRL to find a free weekend in the calendar to hold this game or to negotiate with the BRL to mitigate potential impacts, so the proposed showcase clashed with already scheduled club games.

On top of having to reschedule their games, the rival programme would likely steal paying spectators from the BRL, taking money that should be going to the Brisbane clubs and instead being siphoned off by interfering intercity interlopers. The QRL claimed a mandate to run intercity football as they saw fit and the BRL had no say.

Naturally, this triggered endless letters to the editor in Brisbane’s newspapers with the same tone and tenor of the average Redditor discussing the Super League war, including appeals to act for the good of the game, claims about the relative merits of the leagues and accusations of being afraid to compete, or for that matter, the same tone as used to discuss the merits of a port at Cleveland Point. Some types of guys are forever.

The BRL did not yield and the QRL moved to the Cricket Ground. On May 17, commencing 2pm, Carlton beat Coorparoo, Grammars beat University and Valleys beat Brothers at the Exhibition Grounds, in front of 1,000 people. On the other side of the river, Toowoomba and Ipswich kicked off at 3.30pm in front of 12,000 to 15,000 (reports vary) paying spectators at the Gabba with a gate in excess of a thousand pounds. It was a clear victory to the QRL.

For the next year, 1925, a triangular intercity round robin tournament featuring Brisbane, Ipswich and Toowoomba was scheduled by the QRL. The BRL was seemingly cooperative, although variations on this theme would continue to rear its head down the decade.

After Toowoomba smashed Brisbane at the start of May - these Galloping Clydesdales were coming to the end of a historic unbeaten run, which included wins over touring England and New Zealand sides, New South Wales, Ipswich, Brisbane and South Sydney from June 1924 through the end of the 1925 season - the Queensland Brewery put up a 25 guinea silver trophy (about $2,500 in today’s money) to be awarded to the winner of the series.

The Bulimba Cup was born.

The series was a fantastic success and became a focus of the calendar, forming a representative link from local A grade to the Maroons and Kangaroos. Each city carved out their own identity. Ipswich were the perennial underdogs in green, Brisbane were the poncy, poinsettia metropolitans in cherry red and Toowoomba were the country Clydesdales clad in blue. In marking the 50th anniversary of the 1963 Bulimba Cup, Bernie Pramberg noted:

After a torrid rugby league Test match in the 1960s, a battered and bruised Australian forward made a comment to feisty halfback Barry Muir.

“You won’t get many games tougher than that,” he said.

Muir replied: “You haven’t played Ipswich in Ipswich.”

…

Des “Tractor” Tracey was a 19-year-old second-rower making his debut for Ipswich and prop Ray Verrenkamp was a seasoned campaigner who had earned his stripes alongside the likes of internationals Noel Kelly, Dud Beattie and Gary Parcell in the Ipswich club competition.

“I can remember every minute of the game,” Tracey said. “I’d wanted to run out for Ipswich ever since I was a little bloke going to watch Bulimba Cup games with my mates after junior footy on Saturday mornings.

“Ipswich’s game always revolved around tough forward packs, Toowoomba had the brilliant backs and Brisbane thought they had everything.”

From 1925 to 1950, Toowoomba won the cup six times, Ipswich eight, including seven from 1929 to 1939, and Brisbane 12. After half a decade of Brisbane dominance in the back half of the 40s, Duncan Thompson, a former Kangaroo who had led North Sydney to their only premierships before helming the Galloping Clydesdales, and the unfortunately nicknamed ES Brown revived Toowoomba’s fortunes, winning six Cups in a row. As Thompson wrote in his book:

Rugby League was in a depressed state in Toowoomba in the late 1930s… the ‘Galloping Clydesdales’ might never have lived…

Toowoomba is a proud city. Memories of the 1920s and 30s, when man for man Toowoomba supplied a greater number of players to Australian teams than any other city in the country, were becoming embarrassingly dim. In the Bulimba Cup competition, Toowoomba was something of a joke. We were a pushover.

In 1950, I went to [ES Brown] and asked him to become the president of the Toowoomba Rugby League… He would take the job provided I became the coach… I agreed to coach and together we formulated a three year plan to win back the Bulimba Cup.

It is history now that we did it in two years and held on to it for the next five. So for six successive years Toowoomba again was ‘top dog’ in Rugby League in Queensland.

Thompson attributes the 1950s Clydesdales’ success to:

his cerebral brand of coaching, including fourteen lectures that all players were expected to be able to recite from memory on the spot in front of his comrades,

the tactics of Contract Football, what we might call passing, teamwork and a sense of cohesion today but with a more rigorous intellectual framework behind it,

Thompson’s connections to former Sydney players that were employed to find fringe first graders to come to Toowoomba, and

restructuring the local competition by reducing the number of teams from six to four, improving the quality of week-to-week competition and thinning out the meatheads who couldn’t handle Contract.

Thompson opened a sporting goods shop in Toowoomba after his retirement in 1925 and became one of the two main coaching influences on Wayne Bennett, along with Northern Suburbs’ Bob Bax.

During his eulogy for one of the founders of the Brisbane Broncos, Paul “Porky” Morgan, Bennett spoke about how he and Morgan had first met:

I first met him in 1970 in Toowoomba. I was a young policeman and Paul was working for a fertiliser company. We were both playing for All Whites. That was the last year Toowoomba won the Bulimba Cup against Brisbane. Paul was in the team and I was on the bench…

Then in 1987 someone mentioned that Brisbane were to be admitted to the NSW Rugby League and in charged Paul with his partners, Steve Williams, Barry Maranta and Gary Balkin, to form the Broncos. He became an owner and a foundation member of the Broncos because he wanted rugby league to grow, to be promoted as he believed it should be. He never did anything second rate, that was not his way.

I was all settled in Canberra when Paul Morgan arrived at my home at 8.30am one day with my accountant in tow. I answered the front door and there was Paul holding this big port. I asked what he was doing in Canberra and what the port was for. “You keep rejecting my offers to coach the Broncos,” he said. “I am staying at your home until you say ‘yes’.”

Four hours later, with a headache, I went for a run and decided that I would take the job.

The results of that partnership do not need restating in full but, briefly, the Broncos, Super League, the NRL and many premierships are all downstream of the Bulimba Cup.

The arc of history is long but, like the Brisbane River, it bends around Bulimba.

In 1961, the Carlton and United Breweries of Victoria came north for a second time. After purchasing a brewery in Cairns in 1931, CUB made an offer for Queensland Brewery Ltd. Bulimba Gold Top, the Bulimba Cup and five of the six breweries in Queensland were now in Victorian hands.

This was not novel. The Castlemaine in Castlemaine-Perkins refers to the Victorian town where the Castlemaine Brewery had first started before moving north via Sydney, Melbourne and Newcastle. The Perkins family that ran the City Brewery originated in Victoria before taking over a brewery in Toowoomba and then moving to Brisbane. Those two merged in 1928 and then the joint venture merged with New South Wales’ Tooheys in 1980.

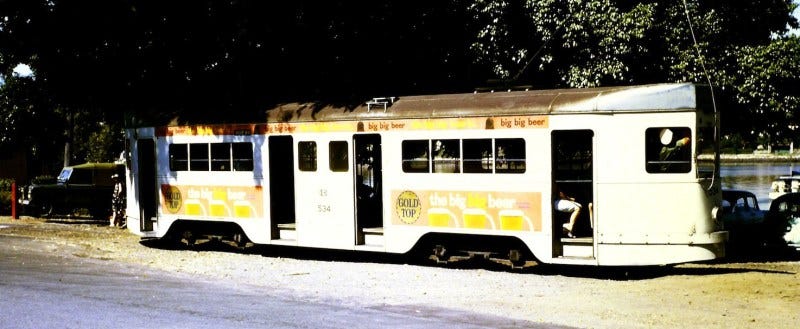

The new owners brought some fresh thinking. For example, a TV ad with a catchy jingle and tagline debuted in 1965.

The original big big beer was not Vic but Gold Top:

Legendary creative Bruce Jarrett, from Australia’s biggest agency, George Patterson, was called in.

Bulimba’s big, big beer, for a big, big thirst was born, and well-known Australian actor John Meillon was recruited to flog it.

The ad went down a treat, but the beer didn’t.

“It was a dog of a beer,” Mr Jarrett recalled.

Dog or not, the campaign was stunningly popular:

“We need something that takes over Brisbane, something really BIG”. I knew it had the potential of being one of the biggest advertising campaigns ever to hit the sunny state. I also knew we had to have a pool of commercials, not just a one-off spot.

I had never written for beer, but, fortunately, I knew Brisbane and Queensland and realised the campaign had to have plenty of guts.

The consonant ‘B’ is the most masculine in the English language and I was lucky having two them in Bulimba. I then added the words brewed by and I had two more. I worked at taking the ‘B’ theme even further. And so the big big beer came into being….

I wanted something big, rough and gutsy, something like the music used in the then current Magnificent Seven movie.

John Meillon was my first choice for the voice and as soon as he heard the music track he went for it, almost perfect from take one. He could be laid-back but come on strong when needed. Client approved the campaign without a word change and so I wrote the pool-outs, a batch of 60’s and 30’s and we went into production…

First night we launched with twelve 60’s on each channel in prime time backed with three broadsheets in the Courier Mail: First: A big big thirst Second: Needs a big big beer Third: And the big big beer is Gold Top, brewed by Bulimba.

Within a couple of weeks Gold Top was outselling XXXX, the track was being played free of charge on juke boxes in pubs and clubs. It had taken over Brisbane. Woolworths Brisbane phoned to ask where we’d bought the beer glass used in the spots. I had gone shopping and found a Scandinavian glass mug in a small gift shop which I thought looked right – it has to be glass to show the beer but I wanted something heavier than a regular beer glass. Woolworths copied it and named it The big big beer glass.

George Patterson recycled the campaign for the Victorian market two years later.

At that time, beer marketing and advertising was pretty unsophisticated as CUB had a virtual monopoly. Draught beer in pubs was unbranded, patrons simply asked for “a beer”. CUB’s packaged products had no defined positioning and no real brand values.

George Patterson Melbourne had the responsibility of determining and writing these strategies for CUB’s four big products at the time – draught beer, which became Carlton Draught, Foster’s Lager, Melbourne Bitter and Victoria Bitter. It’s interesting to recount that an early recommendation was to brand the draught beer product VB.

The George Patts team discovered that the product and consumer profiles for VB exactly matched those for Bulimba Gold in Queensland – blue collar, honest toil and reward for a hard day’s work. They had the perfect advertising campaign and strategy in the can. All they had to do was change the name!

By the 70s, Queensland Brewery in the Valley, Castlemaine-Perkins in Milton and CUB in Cairns were the only breweries operational in Queensland.

The Bulimba Cup was on its last legs. Brisbane won seven of the ten Cups in the 1960s. Crowds that had peaked around 20,000 had fallen catastrophically to just a few thousand.

The greater population of Brisbane was a commercial boon to its football clubs, one that could not be replicated by the leaner demographics of Toowoomba or Ipswich. The city of Brisbane’s population was generally eight to ten times that of the other towns. In 1933, Brisbane had a population 130,000 greater than Ipswich or Toowoomba. By 1971, this deficit had grown to 640,000 with Brisbane nearing a million people. The Brisbane clubs were able to lure away the best players from Ipswich and Toowoomba at the expense of the competitiveness of their Cup teams.

The final straw seems to have been on-field violence that plagued rugby league until it became a TV sport:

And in 1971, brewery manager Tom Kelly threatened to withdraw sponsorship following a brawling Lang Park match in which referee Tom Barett sent off four players…

“The way it looks today, if I am presenting this Cup again next year it will be at Festival Hall,” he said. “Wake up to yourselves, don’t fight. Play football or there will not be a Bulimba Cup to play for next year.”

While there would be a Bulimba Cup to play for in 1972, that would be the end of the competition. Brisbane won the final in crushing fashion, 55-2, over Toowoomba in front of just 3,500 spectators. It was a decisive but pyrrhic victory for the BRL.

Queensland teams began playing in the NSWRL Amco Cup1. In their first attempt in 1975, Brothers, Souths, Norths and Ipswich were all knocked out in the first round, while Valleys eliminated Toowoomba in the second before the Bluebags succumbed to Parramatta in the quarter finals.

Over the next few seasons, all eight BRL clubs and six country representative sides would enter. In 1978, Easts Tigers were the last of 14 Queensland teams still standing, having beaten North Sydney in the fourth round, the sole interstate victory for the Queensland sides, before losing to Manly in the quarters. Brothers were hammered, 49-0, by Newtown in the second round, Illawarra beat Norths, 44-5, and Parramatta defeated Wests, 28-0.

There is a very heavy-handed irony in the Brisbane league using its money and population to destroy its local rivals and in turn finding themselves at the wrong end of even richer and more populous Sydney clubs. C’est la vie.

To boost competitiveness, combined Brisbane and Queensland Country teams were entered in 1979. A Brisbane team that featured Wally Lewis, Mal Meninga, Gene Miles, John Ribot, Bob Lindner, Bryan Neibling, Wally Fullerton-Smith and Greg Dowling won the trophy in 1984. All played and won State of Origin for the Maroons that year.

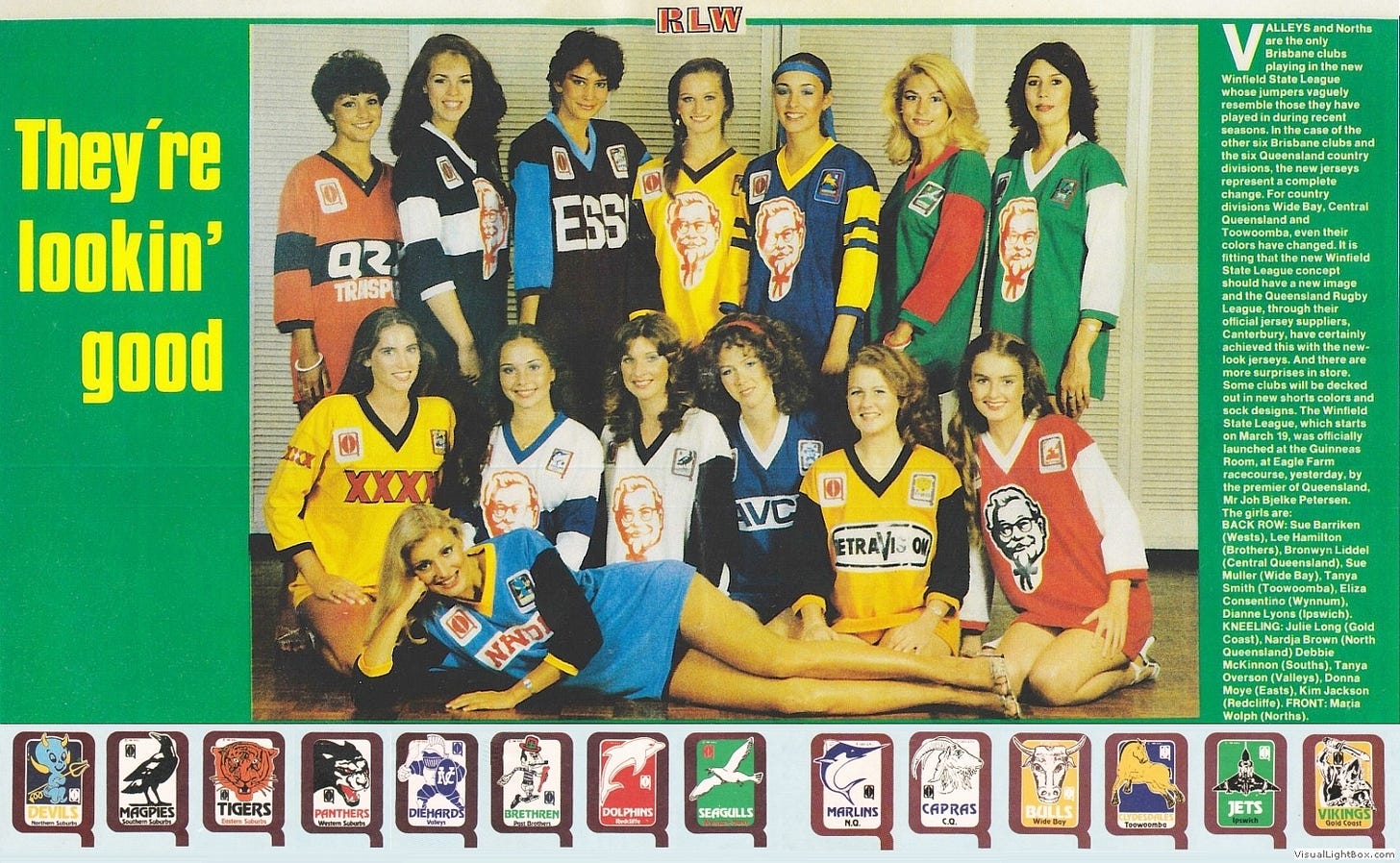

It would also be the last time a Queensland Country team was entered. The QRL introduced the Winfield State League in 1982, which ran until 1994 - won by the Rockhampton Rustlers, the last major statewide trophy won by a Central Queensland team - under varying formats before being superseded by the Queensland Cup in 1996.

The Queensland Brewery site in the Valley shut down in the early 90s. Gold Top had disappeared sometime in the 80s, although no one seems sure exactly when, but presumably few noticed or missed its absence, preferring XXXX or having Victorian beer foisted on the state by CUB.

In one of a series high profile corporate takeovers that erased any sense of regionality in Australia, Alan Bond took control of Castlemaine-Perkins in 1985. Bond incurred the ire of Queenslanders by removing the XXXX sign from the Milton brewery, installing a Bond Corporation logo in its place, while replacing the Milton address with Bond’s Perth headquarters on cans. These changes were soon reversed. Bond later went bust and sold Castlemaine Tooheys to New Zealand’s Lion Nathan in 1992. Since 2009, Lion and XXXX have been part of the Kirin keiretsu.

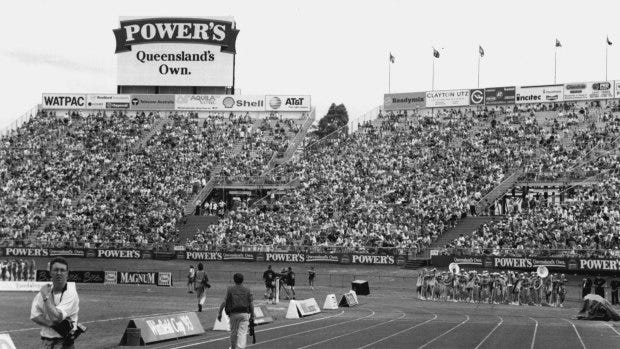

Fed up with these corporate machinations, solicitor Bernie Power built a large, modern brewery at Yatala. Power’s Brewing was to challenge the stagnant and consolidated Queensland beer market. Power’s was listed by Paul Morgan’s stock broking company - Morgans is still in business - and became the front of jersey sponsors of the inaugural Brisbane Broncos in 1988. The pairing of Broncos and Power’s, who had yet to play a game or sell a beer respectively, was the biggest sponsorship deal in Australian sport to that point, reportedly $1 million a year (about $2.8m now) for three years.

The deal was a source of friction between the Broncos and the QRL. Power’s did not have pouring rights at Lang Park - who else but XXXX? - so the Broncos were unable to advertise or sell their primary sponsor’s product at home games and had to be inventive to find additional opportunities. Holding the halftime meeting on the field under conspicuously branded tents was one attempted remedy.

This friction led to the Broncos leaving the QRL-entrusted Lang Park for the Brisbane City Council-owned QEII Stadium in 1993, where the Broncos were afforded more commercial freedom. Brisbane returned to the newly redeveloped Suncorp Stadium, now under the control of the Queensland government, in 2003.

Power’s was able to capture up to 20% of the Queensland beer market in a few short years but the facility at Yatala was unable to keep up with demand from the start. The company struggled financially, triggering a sale to CUB. The sale coincided with the closure of the Valley brewery. The Yatala brewery still operates, and at one point in the 2010s, produced a quarter of the nation’s beer.

In 2011, CUB re-released Bulimba Gold Top. The marketing copy related that “Bulimba Gold Top was first brewed in 1898 in the Bulimba Brewery on the east bank of the Brisbane River beside where the Oxford Street Ferry Terminal still stands today,” which, as we know, is wrong. The beer was first brewed in Bulimba, near the ferry terminal, but on the western side of the river and production moved to the Valley eight years later.

The release of Gold Top and Brisbane Bitter followed CUB’s very successful revival of the Great Northern brand2, notionally based around that Cairns brewery purchased in 1931. The revivals were cynical. Australian trademark law operates on a ‘use it or lose it’ principle. If CUB wanted to prevent anyone else from making Bulimba Gold Top, and profiting from that association, then CUB - the conglomerate having been sold to SAB Miller in 2011, Anheuser-Busch InBev in 2016 and finally purchased by Asahi in 2019, the same year Asahi purchased Brisbane’s Green Beacon Brewing - would have to sell some Bulimba Gold Top.

The new Gold Top bypassed me at the time because the release was not especially wide and I was just starting out on becoming a craft beer wanker. Nonetheless, a few years later, and two writing projects ago, I wrote a lengthy post on the history of Bulimba Gold Top.

For reasons that aren’t clear to me now, it had really just captured my imagination. I don’t have any direct memories of Bulimba Gold Top or anyone in my family talking about it. Possibly none of them had even tried it. Then again, all of my grandparents emigrated to Australia from the UK in the 60s and I’m the first person in my family to be born in Queensland, so it may have passed them all by. And yet here we are.

In the decade after I wrote my history, I drank beers labelled Bulimba Gold Top no more than two times. One was at what used to be called the Elephant Arms Hotel in the Valley (now the Prince Consort) and it was awful, possibly drawn from a dusty keg leftover from the 2012 release that some enterprising bar manager had found out the back of the cold room. The other was at the Waterloo Hotel in the Valley and it was fine, pretty much like XXXX Gold.

Given neither of these appear in the 866 beers3 that I have tried between April 2013 and January 2016 and then infrequently since the start of 2024, as recorded on my Untappd account, that suggests these events happened circa 2018. Unlike the 2011 release, there’s absolutely nothing about these beers on the internet from this time, which gives you an idea of how little CUB cares about the product. It is like finding the world’s most esoteric and least palatable easter egg six years after it was hidden.

Now that we are closing in on 6,000 words at this point4, you’ll understand why my eyes bugged out on seeing this box at Dan Murphy’s in Strathpine in December 2025.

Green Beacon, CUB nor Asahi have provided any information, not even a cutesy press release, about this beer. The only reason I know I’m not hallucinating the beer’s existence is that other people have checked it into Untappd. It is not clear where you can buy Bulimba Gold Top - there is no listing on the Dan Murphy’s website or the Green Beacon online store - or why it was brought back or how long it will last. For all intents and purposes, it may as well not exist. Given releases in late 2011, sometime around 2018 and now late 2025, we probably won’t see it again until the Olympics.

Power’s has enjoyed a similar resuscitation in 2023:

And the relaunched beer has fans in the Brisbane on-premise too, with owner of the Pineapple Hotel, Bob Singleton, saying: “Queensland is ready for the return of a state-based brand and Power’s is a brand that is Queensland to its core. Power’s is simply a great story that will bring back great memories for people of when Queenslanders got a unique beer they could truly call their own.”

“But I’m just as excited about how good it tastes. The new liquid in the bottle is as good as the story behind it!”

Undoubtedly, the beer in the 2025 can has nothing to do with Gold Top5 as it was brewed in the 1900s, the 1930s, the 1960s or when it was finally discontinued in the 1980s. It is decidedly different from both 2010s iterations. Keeping the mark doesn’t require the beer be faithful to some idyllic past recipe or require that the beer even be good. Anything could be used to fill the cans as long as the IP was used to sell the contents.

In either case, if it was clear if these were intended to be recreations, or not, it would be impossible to do so authentically. The character of the water supplied to Brisbane was irrevocably altered by the construction of Wivenhoe Dam, never mind the changes to treatment technology employed by the city when water was supplied from Enoggera. The malting process is now rigorously homogenised and automated, as is the growing of the grain. Most of the hop varietals used in the 2025 version were only developed in the last half century and bear little resemblance to English and German antecedents.

For the record, the newest version of Gold Top is quite good. The irony is I went looking for Mountain Goat Summer Ale (another Asahi-owned brewery) and this beer is very similar to the point I wonder if they just swapped some labels. Gold Top has a slightly deeper amber colour than its contemporary revivals, is relatively light on the malt with a hint of caramalt in the background, befitting a “craft” beer, and is relatively heavily dosed with a melange of esthery new world hops, an emphasis on the fruit than the bitter. At 4.2%, it hits the exact ABV to minimise excise obligations while optimising focus group feedback.

Power’s and XXXX are different enough from each other that you might be able to identify them in a blind taste test - Power’s is a hint maltier and marginally less bitter -but need to be drunk in an extremely narrow, and cold, temperature window, lest you get some of the other flavours hidden under the bubbles. There is a familiar Pride of Ringwood bitterness and the congeners that arise from the intersection of Sacchromyces and cane sugar that are the hallmarks of beer from this part of the world.

Like the tram tracks that run down Old Cleveland Road, or their occasional excavation in the city, or becoming obsessed with the Fitzgerald Inquiry last summer, Bulimba Gold Top, the Bulimba Cup, the old footy grounds around Brisbane, beer and rugby league are all hints of a past that I didn’t directly live (and am not nostalgic for) but weigh on the edge of my lived experience.

The ephemera of the past lingers, informing the present but never showing itself. It can’t, because the past is gone. As annoyingly omnipresent as consumerism is, the packaging, the signage and the branding of everyday items and events is part of the colour and shade of day-to-day life. Memorialisation of the ordinary helps us to remember where we’ve been and figure out where we’re going. Not all traditions of dead generations weigh like a nightmare.

Later the Tooth Cup - the same Kent Brewery Teeth, yes - and Panasonic Cup.

Itself a response to the success of XXXX Summer Ale - remember those? Very high post-GFC, Naked and Famous, house party vibes.

It’d be fascinating to know how many are from breweries that are still operating and how many were just a few hectolitre limited releases. I’m guessing it would be a very low percentage of beers that were ever all that widely available and even lower still that are available at all now. The first check-in was Murray Brewing Co’s Punk Monk, a beer I have a very vague recollection of, but Murray sticks in the mind because of an oyster stout they used to make, which is exactly what it sounds like. Beer used to be fun. Now it’s all XPAs.

And somewhat lengthier than the first history I wrote.

This is probably less true for the Power’s.

First class writing

This was bonkers. I hope you don't get arrested.